Black-Capped Chickadee

Black-Capped Chickadee Common Raven

Common Raven American Oystercatcher

American Oystercatcher Piping Plover

Piping Plover Willet

Willet Herring Gull

Herring Gull Great Black-Backed Gull

Great Black-Backed Gull Least Tern

Least Tern Roseate Tern

Roseate Tern Osprey

Osprey American Black Duck

American Black Duck Marsh Wren

Marsh Wren Saltmarsh Sparrow

Saltmarsh Sparrow Seaside Sparrow

Seaside Sparrow Brown Creeper

Brown Creeper Winter Wren

Winter Wren Veery

Veery Northern Waterthrush

Northern Waterthrush Canada Warbler

Canada Warbler Wilson's Snipe

Wilson's Snipe American Bittern

American Bittern Least Bittern

Least Bittern Northern Harrier

Northern Harrier Swamp Sparrow

Swamp Sparrow Common Merganser

Common Merganser Common Loon

Common Loon Ruffed Grouse

Ruffed Grouse Black-Billed

Black-Billed Eastern Whip Ppor Will

Eastern Whip Ppor Will American Woodcock

American Woodcock Least Flycatcher

Least Flycatcher White-Throated Sparrow

White-Throated Sparrow Blue-Winged Warbler

Blue-Winged Warbler Nashville Warbler

Nashville Warbler Mourning Warbler

Mourning Warbler American Redstart

American Redstart Chestnut-Sided Warbler

Chestnut-Sided Warbler Black Vulture

Black Vulture Northern Goshawk

Northern Goshawk Broad-Winged Hawk

Broad-Winged Hawk Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker

Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker Blue-Headed Viero

Blue-Headed Viero Red-Breasted Nuthacth

Red-Breasted Nuthacth  Golden-Crowned Kinglet

Golden-Crowned Kinglet Swainson's Thrush

Swainson's Thrush Purple Finch

Purple Finch Hermit Thrush

Hermit Thrush Pine Siskin

Pine Siskin Evening Grosbeak

Evening Grosbeak Dark-Eyed Junco

Dark-Eyed Junco Black-and-White Warbler

Black-and-White Warbler Magnolia Warbler

Magnolia Warbler Pine Warbler

Pine Warbler Yellow-Rumped Warbler

Yellow-Rumped Warbler Black-Throated Green Warbler

Black-Throated Green Warbler Rose-Breasted Grosbeak

Rose-Breasted Grosbeak Vesper Sparrow

Vesper Sparrow Bobolink

Bobolink Savannah Sparrow

Savannah Sparrow Common Tern

Common Tern

Massachusetts

Birds

at Risk

Climate change is putting some Massachusetts birds at risk. Hotter temperatures, rising sea levels and urban development are threatening species and pushing them out of their habitats, and in some cases, out of the state.

A World Without Birds

Canary in the Coal Mine

Through the 1900s, miners caged canaries into coal mines to detect toxic gases like carbon monoxide because birds were more sensitive to the gases than humans. The miners would work and listen for the canary. If the canary stopped singing and died, the miners would know if the area was too toxic and would get out.

In 1962, scientist Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, a book about a future in which pesticides and chemicals had damaged the wildlife so much that a spring would come with no bird song, no buzz of bees—no sounds of natural life.

The Black-capped Chickadee

Massachusetts chose the Black-capped chickadee as its state bird because of its suitability for the New England climate, its singing, and its friendly demeanor.

But changes in climate, especially warming temperatures and rising sea levels, might push the bird out of the state.

Jennifer Ackerman said in her recent book, “The Genius of Birds,” that “the chickadee is more than just the bird of verve and agility. It’s also acrobatic in its aptitudes, curious, intelligent, opportunistic, with a remarkable memory.”

She goes on to explain that the number of “dees” at the end of the black-capped chickadee’s song can convey the size of the predator approaching and whether it is on land or in the air—making it one of the most advanced forms of animal communication.

The Black-capped Chickadee in Massachusetts

Pull the slider to see the change.

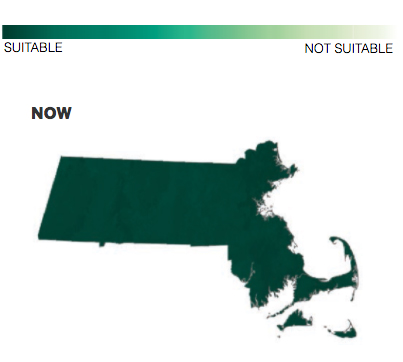

Maps published by Mass Audubon that show the current and projected distributions of different birds show the Black-capped Chickadee moving further north and away from the state as the climate changes.

According to a State of the Birds report published by Mass Audubon earlier this fall, by 2050, the Black-capped Chickadee’s likelihood of occurrence in Massachusetts will drop from 52 percent to 22 percent. *

Maps published by Mass Audubon that show the current and projected distributions of different birds show the Black-capped Chickadee moving farther north and away from the state as the climate changes.

Highly Vulnerable Birds

But changes in climate do not just affect a single bird. The study looked at the current habitats of 143 bird species in Massachusetts and, based on a number of factors, predicted whether the shifting climate will allow for hospitable habitats for those species. It classified 43 percent of the species evaluated (61 in total) as “Highly Vulnerable” by the year 2050.

To determine the “Highly Vulnerable” classification, Mass Audubon compared how likely a particular species is to occur nowadays versus the prediction for the year 2050. The species likely to drop to under 80 percent were labeled “Highly Vulnerable.” The Black-capped Chickadee’s likelihood to occur is predicted to drop to 42 percent of its current ranking.

Also listed as “Highly Vulnerable” are birds such as the Saltmarsh Sparrow, which dwell in salt marshes, the Piping Plover (a federally listed threatened species) in coastal habitats, the Ruffed Grouse living in mature forests, and the Common Raven, which shares urban and suburban habitats with the Black-capped Chickadee.

Climate Change's Impact on Birds

A Birder's Eye View

Chad Witko’s fascination with birds began at age two or three in Hudson Valley, New York, when his father, a waterfowl hunter, would bring home ducks and geese that he had harvested.

Witko loved feeling the soft feathers and the hard bills of the ducks. “The colors really captivated me as a young kid.”

Now Witko is a graduate student in Conservation Biology from Antioch University New England in Keene, New Hampshire. He also is a birder for the Antioch University Bird Club and an editor for eBird, an online database of bird observations.

He’s been birding for about 33 years, though on a more intensive level for the past 20. And though he’s not a morning person, he drags himself out of bed early just to explore the world of birds.

“As someone who has had birds intimately in my life through the last few decades, birds are as much as my reality of the world as the sky is for anyone else. And for me, a world without bird would be kind of like a world without wonder and a world without hope,” said Witko.

He and the other members of the Antioch Bird Club travel all over the New England area during all seasons, looking for, appreciating and entering information about many species of birds. They even have contests to see who can see the most species of birds throughout the year.

Veteran birders like Witko learn the specific songs of birds and will pause in the middle of a conversation to listen for specific calls. In order to get birds to come to them, they will use “pishing” or “spishing,” where they mimic an alarm call to make birds come check out what the threat is.

In the time that he has spent birding, he has noticed that some birds are appearing less and less frequently, while some southern birds are present in northern areas when they shouldn’t be. As a biologist, these changes worry him about the future.

“Birds are great ecosystem indicators, and they teach us so much about the world. By seeing what they’re doing, I get a sense of how the world’s doing,” said Witko.

Specifically, he expressed concerns about the salt marsh sparrow. He explained, “It’s a species that some people predict might be extirpated in the next 50 years if sea level rise continues.”

However, although his work as a conservation biologist has allowed him to see a lot of the damage to the environment, it has also given him some hope that individuals are taking action to make a difference.

“ We are screwing up a lot, but we’re also working really hard to change,” said Witko. “It’s really easy to be disheartened. It’s easy to lose sight and to feel like, ‘What good can one person do?’ But it’s important to realize that … every person can do something.”

So what can you do?

Looking Forward

To make their predictions of habitat suitability Mass Audubon used a technique called climate envelope modeling. The technique involved defining the points that different species occupy and do not occupy using datasets of 19 different climate variables, which include temperature and precipitation data. Mass Audubon’s model then predicts how the conditions might change assuming greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase and evaluates whether these future conditions would still represent a suitable habitat for individual species. The report itself contains more information about the model and its limitations.

“The model looks at the current data and then at what could occur in 2050,” said Petersen.